Colonies in the 21st century (II)

German companies are complicit in Morocco’s occupation of Western Sahara in violation of international law. Formerly a Spanish colonial territory, Western Sahara is categorised by the UN to this day as one of the last remaining colonies.

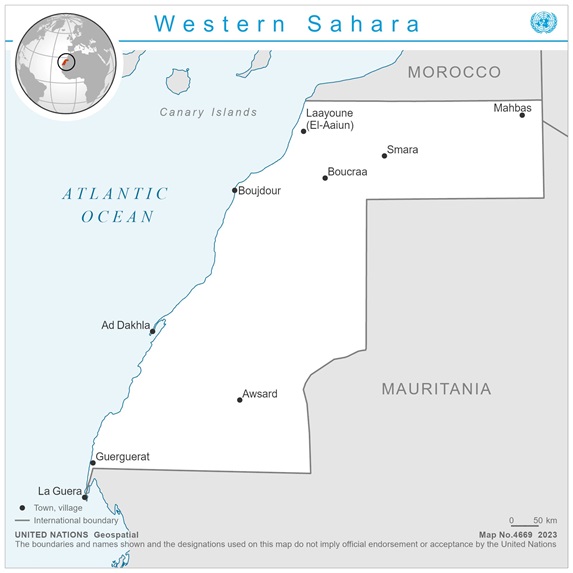

BERLIN/RABAT (own report) - German companies are complicit in the occupation of one of the few remaining colonial territories of the 21st century, Western Sahara, in violation of international law. The territory has been under the control of Morocco for almost fifty years. Tthe International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague ruled in 1975 that Western Sahara, in accordance with its classification by the UN as a ‘territory without self-government’, has the right to self-determination and independence as a state entity. Western Sahara had initially been a colony of Spain from 1884. Under its dictator, Franco, Spain had been repressing a growing anti-colonial rebellion since the 1950s, but finally withdrew from the occupied territory at the beginning of 1976. That was then the signal for Moroccan troops to move in. They continue to illegally occupy and exploit the territory to this day. Only the US and Israel officially recognise Morocco’s sovereignty over Western Sahara. One of the tactics pursued by Rabat to secure Moroccan rule in the face of diplomatic pressure is to involve companies from third countries in the economic plundering of the territory. Among others, German corporations, such as Heidelberg Materials and Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy, have seized this opportunity.

Spain, a colonial power

Western Sahara was delineated and declared a colony at the Berlin Conference of 1884/85. This was the setting for a major carve-up of Africa by the European nations as they arbitrarily divided up large parts of the continent among themselves for conquest and domination. Western Sahara was awarded to Spain, which had previously lost its colonies in Latin America and was about to lose control of Cuba and the Philippines, too. Spain was now looking to secure a colonial foothold in Africa, where, apart from the Canary Islands, Ceuta and Melilla, its main territorial claim was Guinea Española, today’s Equatorial Guinea.[1] Later, the Franco dictatorship renewed efforts to maintain Spain’s rule over Western Sahara, even as a wave of decolonisation and independence was sweeping across Africa. In the 1960s, Spain began to develop the huge phosphate deposits discovered at Bou Craa in 1947 – clearly an incentive for bolstering colonial rule over Western Sahara.[2] However, Madrid would fail in the longer term.

Struggle for liberation

As early as the 1950s, the anti-colonial liberation struggles in Africa, including Algeria and Morocco, had invigorated anti-colonial forces in sparsely populated Western Sahara. There, too, armed resistance was being organised against the colonial power, Spain. Sahrawi aspirations for independence were boosted in 1963 by the decision of the United Nations to include Western Sahara on its list of “non-self-governing territories” – a list of countries awaiting decolonisation. In the early 1970s, fighting against Spain flared up again in Western Sahara. The movement led, on 10 May 1973, to the founding of the Polisario Front (Frente Popular de Liberación de Saguía el Hamra y Río de Oro), a liberation organisation that is still fighting for the decolonisation of the country today. When Spain saw no other option but to withdraw from Western Sahara at the end of 1975, Morocco moved quickly to seize control of the country. Its plans for a ‘Greater Morocco’ at that time even envisaged the conquest of parts of Algeria, Mali and Mauritania.[3]

Morocco, the new Colonial power

On 27 February 1976, just before the official withdrawal of the Spanish colonialists, the Polisario Front proclaimed the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). However, the insurgents were too weak to assert themselves against the Moroccan armed forces, which took over some 80 per cent of the country. In the 1980s, Morocco contained the asymmetric threat from Polisario fighters by building a huge sand wall, reinforced with mines and military outposts. It shields the western two-thirds of Western Sahara, directly controlled by Rabat. In 1991, the United Nations succeeded in brokering a ceasefire between the two sides, with the pledge of a referendum on the independence of Western Sahara. The UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) was established to expedite the process, but a vote has still not been held – not least because Morocco demands voting rights for the many Moroccans citizens who have migrated to the towns in the territory and would prevent a pro-independence majority. Rabat not only failed to hold a referendum but has also broken the ceasefire.

Rabat seeks international recognition

Morocco has long been pushing for international recognition for its control over Western Sahara, even though the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague, on 16 October 1975, declared this inadmissible. The progress made by Rabat in its diplomatic strategy has been modest. So far 38 of the 84 UN member states that once recognised the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic have frozen or suspended their recognition. However, only two states actually recognise Moroccan rule officially. The United States accorded official recognition on 10 December 2020, as one of the last measures taken by the Trump administration. Israel followed suite on 17 July 2023. Morocco has succeeded in persuading a total of 28 states to open a consulate in Dakhla or El Aaiún, the two most important cities in Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara.[4] Moreover, Rabat has been attracting companies from third countries to engage in the economic plundering of occupied Western Sahara. This involves above all phosphate mining and green energy projects.

Raw materials

For decades, Morocco has been mining phosphate near Bou Craa, a site where the Spanish colonial power had themselves extracted the raw material for fertiliser production. Several German companies are involved in resource extraction in various ways. Siemens Gamesa, for example, has supplied 22 wind turbines for the Foum El Oued wind farm, which produces all the power required for phosphate mining. As reported by the advocacy NGO Western Sahara Resource Watch (WSRW), Siemens Gamesa confirmed in 2018 that it had extended its contract to maintain the wind farm for a further fifteen years.[5] According to WSRW, ThyssenKrupp also admitted in 2021 that it had been repairing phosphate mining equipment in Bou Craa. The company refuses to deny any future activities there. Heidelberg Materials (formerly HeidelbergCement) has, for its part, massively expanded its cement production in occupied Western Sahara. This development, which became known last year, involves the construction of a new port facility for exporting phosphate rock and fertiliser.[6]

Renewable energy

Siemens Gamesa is also involved in other wind energy projects in occupied Western Sahara. In 2012, a consortium led by a group that includes Nareva, an energy company owned by the Moroccan royal family, was awarded the contract to build five wind farms: three in Morocco and two in Western Sahara. Siemens Gamesa then built a factory for making wind turbines in northern Morocco, located at Tangier on the Strait of Gibraltar. This facility went into operation in 2017 and is, among other things, equipping the wind farms in Western Sahara. In addition to the Foum El Oued wind farm, Siemens Gamesa has also supplied the Boujdour and Aftissat wind farms and a smaller plant that powers a Heidelberg Materials cement grinding plant.[7] As reported by WSRW, Siemens Gamesa even went so far as to explicitly refer to Western Sahara as part of Morocco in 2020. This openly contradicts the ICJ ruling of 16 October 1975, placing the company above international law.

The ‘free world’ and its order

The Western states, including Germany, are waging a struggle – under the banner of the supposedly ‘free world’ – to maintain the existing world order they dominate. Yet this world still contains actual colonies, most of which are quite openly kept in a state of unfreedom, mainly by Western states themselves. In addition to Western Sahara, german-foreign-policy.com has recently reported on New Caledonia [8] and will look at other examples of extant Western colonies in future articles.

[1] Macharia Munene: History of Western Sahara and Spanish colonisation. In: Neville Botha, Michèle Olivier, Delarey van Tonder: Multilateralism and international law with Western Sahara as a case study. Pretoria 2008. S. 82-115.

[2] P for Plunder. Morocco’s exports of phosphates from occupied Western Sahara. Western Sahara Resource Watch (WSRW) 2024.

[3] Werner Ruf: Marokkos Rolle in Afrika. In: Judit Tavakoli, Manfred O. Hinz, Werner Ruf, Leonie Gaiser (eds.): Westsahara-Konflikt. Zwischen Kolonialismus, Imperialismus und Selbstbestimmung. Berlin 2021. S. 153-171.

[4] Ahmed Eljechtimi: Israel recognizes Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara. reuters.com 17.07.2023.

[5] P for Plunder. Morocco’s exports of phosphates from occupied Western Sahara. Western Sahara Resource Watch (WSRW) 2024.

[6] Massiver Zuwachs für Heidelberg Materials in der besetzten Westsahara. wsrw.org 16.05.2023.

[7] Das schmutzige Geschäft mit der grünen Energie. wsrw.org 22.04.2024.

[8] On New Caledonia, see: Colonies in the 21st century (I).